The REAL Reason House of Dynamite's Ending Fails

WHY A House of Dynamite's Ending Makes No Sense

Despite its technical brilliance, A House of Dynamite fails in its final moments because it violates a fundamental principle of storytelling and human psychology: the 'open loop.'

If you’ve not seen it, spoilers ahead.

Watch My Visual Screenwriting Masterclass

Watch My Visual Screenwriting Masterclass

What Happened: (Spoilers)

Missile threat, countdown to impact, see the same situation three times from multiple perspectives:

Alaskan missile defense base.

STRATCOM in DC

SecDef’s office.

Deputy National Security Advisor running desperately to HQ.

FEMA lady being evacuated.

North Korean expert on her day off at Gettysburg.

President being notified and trying to make a retaliation decision.

However…

There was no ending.

I don’t just mean the ending was ambiguous (like an arthouse film) or that it didn’t end the way I wanted it it. I mean it did not have an actual resolution, no dénouement.

Kathryn Bigelow wanted it that way, though.

This ending—or lack thereof—undercuts everything else that came before it. If you disagree with me, that’s fine, but as a writer and director, I think there’s a fundamental flaw in the approach that the filmmakers took with the ending.

It has to do with a concept I learned in my day job as a User Experience Strategist called “open loops.”

What Went Wrong:

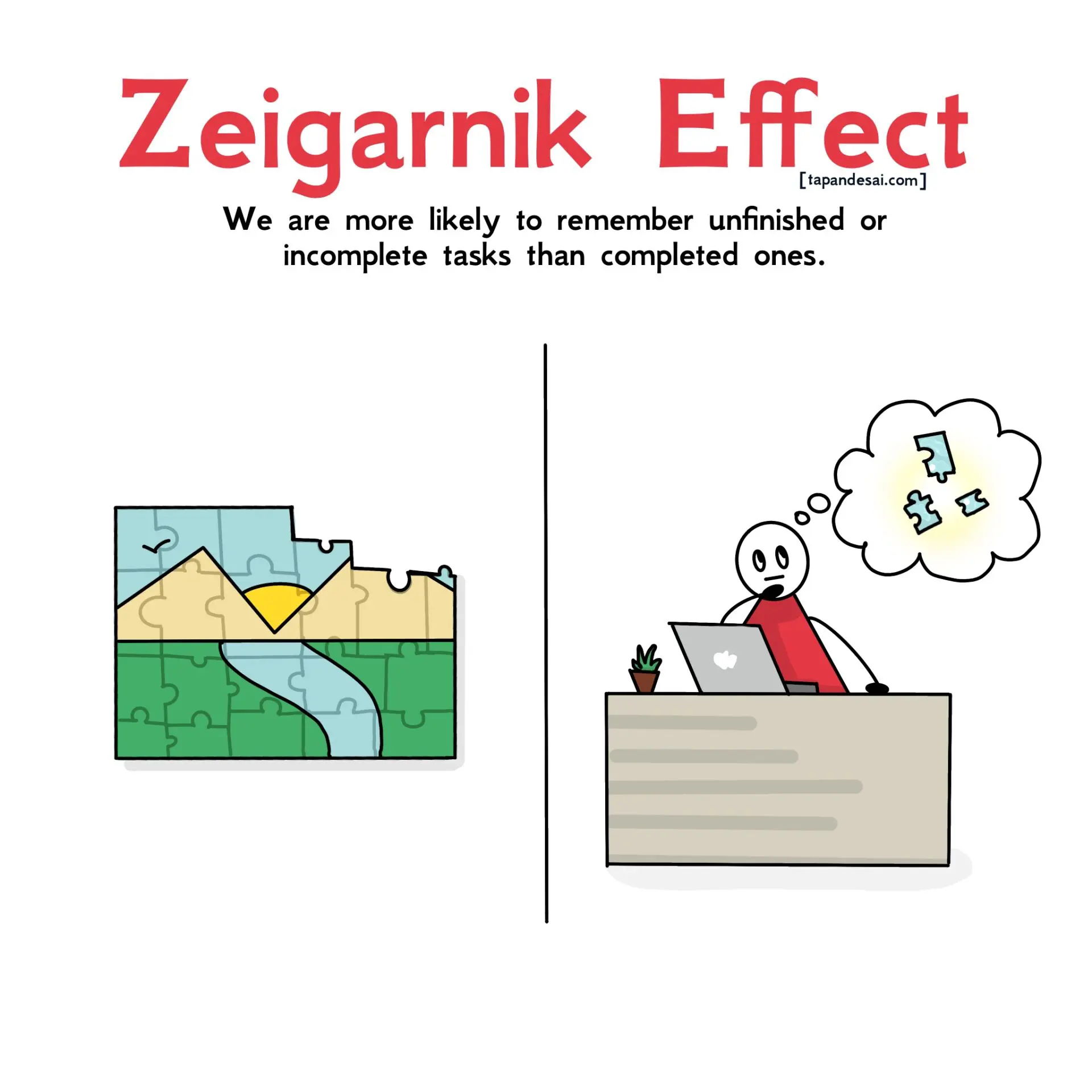

An "open loop" is a behavioral psychology term describing an unresolved mental task or question that stays active in a person's mind, creating cognitive tension or load that burdens memory until the task is resolved or the is question answered.

This is based on the Zeigarnik Effect. Developed by Bluma Zeigarnik, this is the psychological tendency of our brains to remember more about an unfinished task than a completed one.

The Zeigarnik Effect by tapandesai

You can apply this to screenwriting at two levels: First by the main question your audience is wondering based on your first act. These are called Macro Loops. Let me show you what I mean with Pirates of the Caribbean. The central narrative questions are:

Capt Jack: Will Jack beat Barbossa and recover his ship?

Will & Elizabeth: Will Will rescue Elizabeth?

You could boil those both down to: “what will happen at the end?”

then, you can also pose narrative questions throughout your script, keeping the audience engaged to find out the answers. These are your Micro Loops. For example, to continue with Pirates:

Why does Jack have a compass that doesn’t point north?

Will Norrington track down Jack?

Will William become a pirate?

Will Elizabeth’s true identity be found out?

Will the undead pirates ever be made mortal?

Who will double-cross whom?

These essentially keep the audience wondering, “what will happen next?”

These open micro loops drive curiosity and build suspense because they all tie back to the larger Macro Loops, or narrative arcs.

At its heart, the open loop technique is a form of setup and payoff, which is fundamental to great storytelling.

As a story, A House of Dynamite has a compelling concept & perspective: It’s asking us to experience how our nation’s top leaders make incredibly difficult decisions under impossible circumstances. I’ll be the first to say that A House of Dynamite was a well-executed film in the technical sense.

Well-researched

Excellently directed

Solid performances

The whole experience—up until the ending—was a well-orchestrated ticking clock thriller.

Great editing, especially piecing together all the different perspectives throughout the three versions of the scenario. It’s incredibly complex and they pulled it off real well.

Still, this complexity coupled with the many narrative threads ends up creating tons of open loops that the film refuses to tie up. Here are some of the film’s Micro Loops:

The commanding officer at the Alaskan base is having lady problems…

Ferguson’s husband is taking care of their sick son…

The man working with Rebecca Ferguson in STRATCOM is about to propose…

The deputy Natl Sec Advisor’s wife is pregnant…

The bomber pilots who joke about buying toys for kids…

And the worst offender of all: The IT guy.

There was this IT guy in the STRATCOM room fixing the TV when the missile launch alert came, and he looked freaked out, almost like he really shouldn’t have been in the room when this happened but it happened so fast and he just saw more than he should have.

They make it a point to show him sneaking out of the STRATCOM and heading towards an exit, like he was going to spill this hyper-sensitive info to the press room. There’s even another employee who watches him go.

So it’s not just that he runs out of the room scared—we spend time building him up, showing that his actions will be meaningful, and then nothing ever comes of it.

Why It Matters

At its heart, the open loop technique is a form of setup and payoff, which is fundamental to great storytelling. In A House of Dynamite, a lot of things have been set up, but almost none of them are paid off.

It feels the same way for the rest of the characters and their personal stakes; we realize at the end none of these mattered—they were just there to humanize these characters, give them depth outside of their job, to make us care for them

Okay, fine, but if we don’t know what happens at the end to those people, then all these little loops stay open, and we realize that they weren’t open for any larger purpose. These characters don’t have arcs for the most part, either.

The possible exception being when the SecDef—or as I like to call him, Moriarty—walks off a building when he finds out the target of the missile is Chicago where his estranged daughter lives. Even then, we don’t see the aftermath, the impact, with his daughter.

But…the biggest Open Loop is the ending itself. The macro-level narrative question which was built up even more by the multiple perspectives:

what happened to these people?

What happened to Chicago?

Who attacked, and why?

What was the President’s response?

Will the bomber pilots be willing to drop nukes?

It’s like having a four-part TV miniseries where three episodes in a row all end with the same cliffhanger, and you can’t wait to get to the final fourth episode to find out what actually happens—only to discover there IS no fourth episode!

Why no Ending?

As the filmmakers themselves would likely argue, the whole point of their ending is that is IS an open loop. They don’t want to close the open loop so that people will keep thinking about what the ending could have been.

Had this been a stage play, I think that might have worked. It’s a different medium and lends itself to that sort of contemplative, abrupt ending.

However, with the film, instead of audiences thinking about what might have happened, they’re thinking about how they felt at the ending: confused, disappointed, or even angry.

That’s what they’ll remember.

If you dug this movie’s lack of ending, then I get it. It feels edgy, it seems risky—which it is. It’s a bold move from an Oscar-winning director of the highest caliber. I respect that.

Still, I wonder if they did any test screenings of this to see what audiences’ reactions were. At least for my wife and I, when the credits rolled, we just felt cheated.

It didn’t make me want to lean in; it just made me annoyed because I’ll never know what happened in the end. In that way, it had the opposite of its intended effect, which was societal impact.

Outcome Leads to Impact

When I teach film analysis to my undergraduate students, I talk about five ways that film needs to be evaluated from apart from its formal qualities (or artists elements), and one of those is the Outcome.

What happens at the end, and why?

How does the ending make sense of everything that came before it?

Is the ending open to interpretation?

Is the dénouement congruent with the rest of the narrative?

That’s why the ending of your screenplay is so crucial—the outcome informs the rest of the story beforehand. That’s why the best movies get even better when you rewatch them. With AHoD, I don’t think it’ll have that same rewatchability—or impact—because of its lack of outcome.

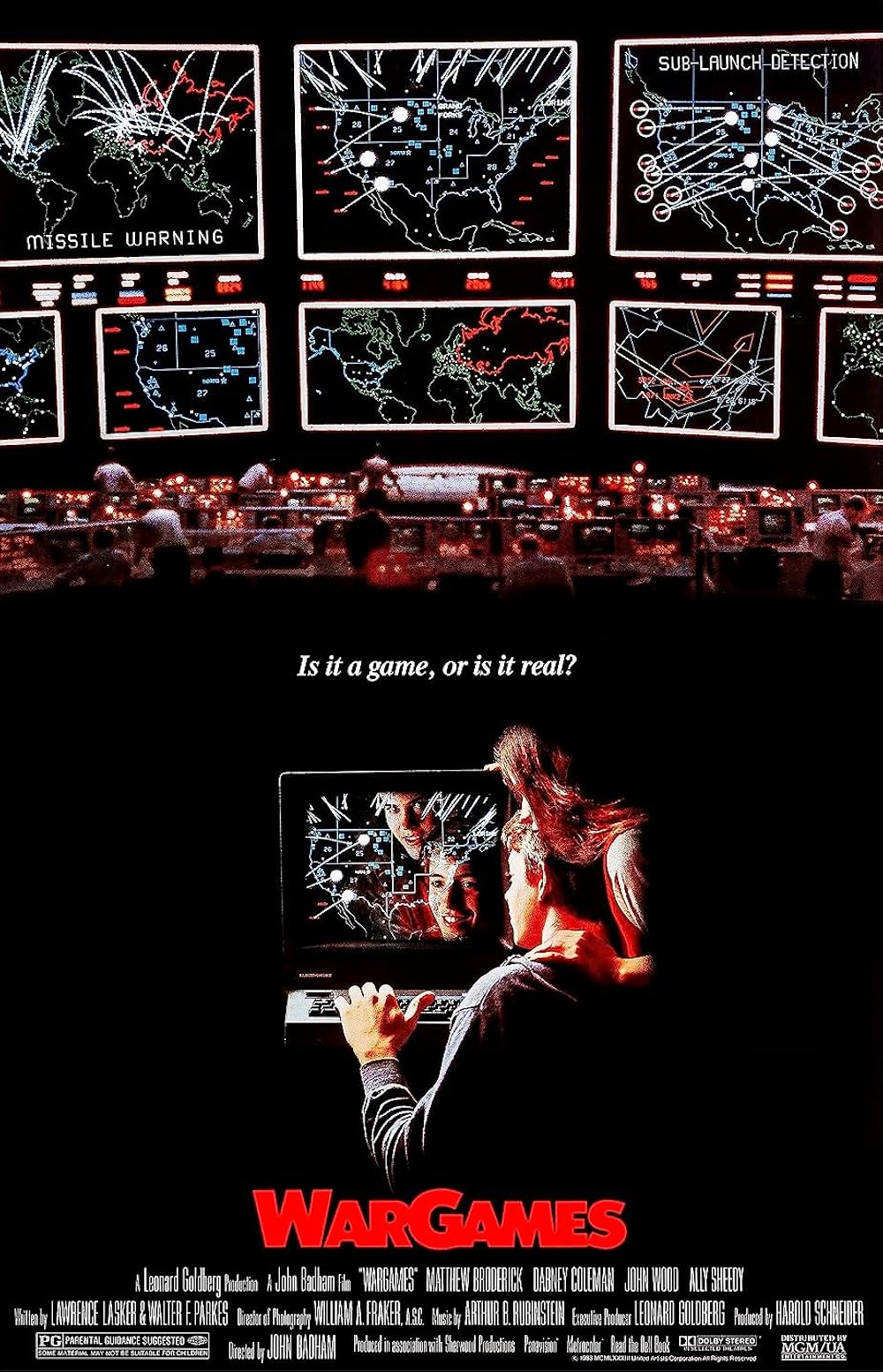

Just to drive this home, let’s compare the “ending” of the 2025 film with a different movie with a somewhat similar concept: WarGames (1983).

In the movie WarGames, a high school hacker accidentally causes an AI computer to think the USSR is attacking the United States and it prepares to launch a counter attack. Since the computer can’t tell the difference between a game and reality, they spend the film trying to stop the computer from starting WWIII.

It has an ending, though. The hacker and a scientist are able to teach the computer about no-win-scenarios through tic-tac-toe, and nuclear war is averted.

This film was just forgotten, right? It’s just another 80s nostalgia film, right?

No, the film had a huge impact when it came out! It even caught the attention of President Ronald Reagan, who screened the film to his staff at Camp David. After he point-blanks asked his national security officials whether such a nuclear hack was possible, his administration issued National Security Decision Directive 145, the first presidential policy addressing what we now call cyber warfare.

The film even led to the creation of the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act of 1986, and kept people talking about the dangers of over-automating nuclear systems without human oversight. Despite the “happy ending,” WarGames influenced government policy at the highest level. I don’t think it would have had such an impact if the ending had been left unfinished.

Why?

Ambiguity vs Confusion: The Critical Difference

Audiences like catharsis.

Audiences want closure.

It’s just hardwired in our brains from the thousands of stories we hear and see every year.

Because they had that satisfying resolution, they were able to leave the theater on a high note, subconsciously remembering the feeling they had while consciously thinking about the concept of automated warfare and mutually assured destruction.

I’m not saying you can’t have ambiguous endings—I’m saying the ambiguous ending still has to mean something. It still needs to be present and give the audience some semblance of closure, or catharsis. Then, because the open loop has been closed, they can think about the deeper meaning behind the ending.

That’s why I brought up UX and behavioral psychology. As a screenwriter, you’re not just telling a story—you’re designing an experience.

Key Screenwriting Lessons from House of Dynamite:

Violates the Zeigarnik Effect: The brain prioritizes unfinished tasks, creating cognitive tension rather than artistic mystery when loops aren't closed (eventually).

Unresolved Micro Loops: Subplots (like the IT guy or family issues) are set up but never paid off, making them feel superfluous.

Lack of Catharsis: Unlike WarGames, which resolved its conflict to create impact, A House of Dynamite denies the audience the emotional release required for the message to stick.